Why the Laird Super Solution? My choice of a subject to model begins and ends with the history associated with it. The history is what attracts me and is the subject of conversation long after the model is completed. Creating a representation of history, that I find meaningful, is the inspiration that provides the juice throughout my creative process.

The seed for the Super Solution was planted during an International Plastic Modelers Society field trip to the National Air & Space museum’s restoration facility in Silver Hills, Maryland during the summer of 1987. The docent was an elderly gentleman who believed “aviation had gone downhill ever since they enclosed the pilot.” During the tour, he pointed to some debris hung from the side of the hanger and explained that was what was left of the Laird Super Solution. He went on to say that he thought it was “the most beautiful airplane ever built.” For some reason that remark stuck with me. I had to look it up because I knew nothing about it. I remember thinking it looked sleek enough, but impractical, because the pilot seemed to have almost zero visibility. Over the years, I would occasionally revisit images of the Super Solution. Eventually I got around to reading about it and right away I put it on my bucket list of future projects.

The sport of air racing in 1931 was entering what had come to be called its Golden Age, an age short in time ... it would last only a decade, but an age intensely long on memory. It was an era noted for its colour and competition, an era of the individualist when designers and pilots alike often put all they had, every dream and every dollar on one airplane.

In this era the little racers served as proving grounds for many new techniques, its wings carried the faith of the future, the 50 feet of air space between it and the pylons became the wind tunnel. The country was in the depths of a depression. Money was hard to come by and only the dedication of a few kept aviation progressing at all.

Prompted by the Laird "Solution's" triumph in the 1930 Thompson Trophy Race, the Cleveland Speed Foundation ordered from the Laird Company a new and faster "Solution"... A "Super Solution". Thus the Foundation indicated their support of a bigger and better National Air Race in 1931. Even in mid-depression such an affair should promote a real financial stimulus.

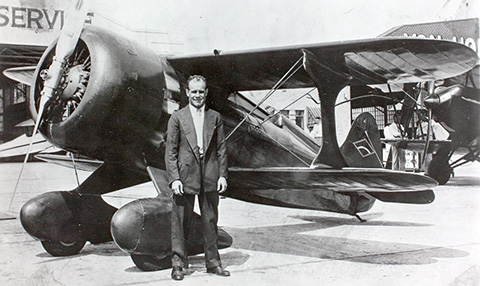

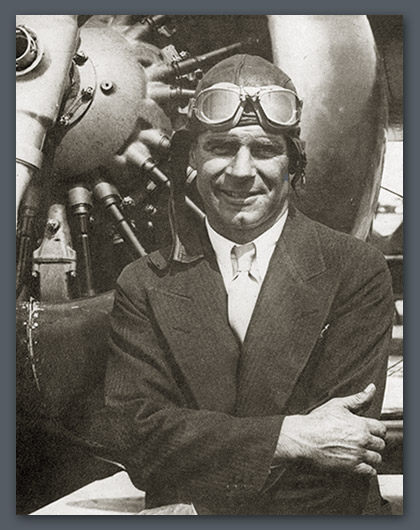

Jimmy Doolittle, then just 34 years old, was already a legend in aviation. His reputation in the field of high speed, cross-country and aerobatic flying was world renowned. He had established an enviable record during his 13 years in the Army Air Service, earned a Doctorate in Aeronautical Science at M.I.T. in record time, won the 1925 Schneider Trophy Race and set a world speed record in the Curtiss R3C-2 floatplane. Resigning from the Air Service in 1930 as a Major, Doolittle accepted a position with Shell Oil Co. as director of its aviation department. He was already a pioneer in blind flying techniques and precision aerobatics. There was no question the Cleveland Speed group had picked the best man to represent them at the controls of their "Super Solution".

The "Super Solution" was simply a refined and more powerful version of the 1930 "Solution". It was the contention of both Matty Laird and his chief engineer, Raoul J. Hoffman, that with refinements and added power the same basic design could be faster than any plane scheduled for entry in the forthcoming National Air Races. Moreover, acting on Doolittle's request, they became convinced they could make it suitable for both the transcontinental Bendix race and the closed course Thompson Trophy Race. Because of the entirely different flying demands, few aircraft designs were ever suitable for both competitions.

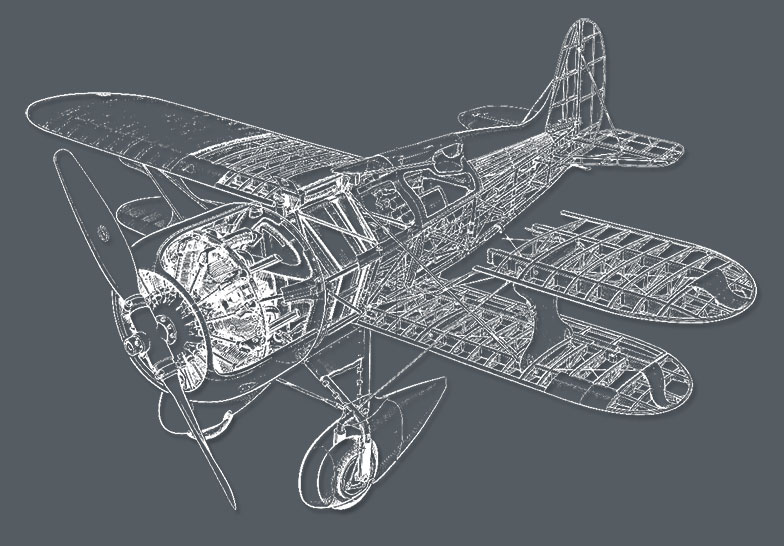

Laird's answer was to design the "Super Solution" to accept two different versions of the same engine, the Pratt & Whitney Wasp Jr., so successful in the "Solution". They would use a geared Wasp for the full out power demands of the Thompson race and a direct drive version for the high altitude and steady power needed in the Bendix. Both engines were specially modified versions of what later became well known as the standard 420/450 hp P & W R-985 Ol the civil model Wasp Jr. S2A which was then commercially rated at 375 hp. However, for racing in which engine life was not a principal factor, the popular Wasps were often over-boosted and used "doped" fuel with a high lead content. The "Super Solution's" engines differed from stock by using high compression pistons and doped fuel. Laird was willing to risk engine failure and short engine life, but in return both of the engines developed well over 500 hp. In fact, the direct drive Wasp delivered 510 hp at 2400 rpm driving an 8 ft. 2 in. propeller, while the 3:2 geared engine, swinging a 9 ft. propeller, could develop up to 560 hp (according to Doolittle's later report. P & W rated it at 525 hp). The geared engine also ran much cooler than the direct drive model.

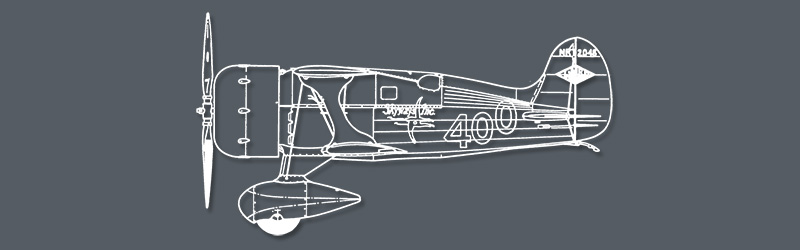

Work began on the "Super Solution" July 8, 1931. Construction went forward with a minimum of delay since most of the major components were identical to the previous year's "Solution" racer. Since the air races were scheduled two months later over the Labour Day holidays the first weekend of September, the "Super Solution" did not undergo the 21 days crash program as had the "Solution". Within six weeks, on August 22, the veridian green and Kodak yellow racer was rolled out for flight tests. She looked like an entirely different plane, yet her wings, tubular fuselage framework, and engine mount were all identical to the "Solution's".

The test flight was made by "Mattie" Laird at Fishborn Field in Chicago, near the Laird Factory. Laird said that very few changes or adjustments were needed before the ship was turned over to Jimmy Doolittle. Visible changes were smaller horizontal stabilizers and elevators and the wing strut fairings. Normal struts appeared on the ship during the test with "I" struts being added later.

The LC-DW500 (LC-for Laird Commercial; D-for series; W-for engine (Wasp); and the 500 for horsepower) as fitted with complete instrumentation for cross country and blind flying, which made it about 200 lbs. heavier than the 1930 Laird Solution (LC-DW300). Because of the monoxide fume trouble encountered by Holman in the "Solution", the Super Solution featured a new fresh air system. This consisted of two vents placed at the leading edge of the top wing, well outside the range of engine exhaust, which channelled fresh air into the cockpit. The streamlining was carried out more thoroughly with a completely enclosed cockpit consisting of three members. The upper member was mounted on a track and moved fore and aft to make contact with the headrest. The side members were hinged about halfway down the side of the fuselage with the upper edge forming part of the track on which the upper member moved.

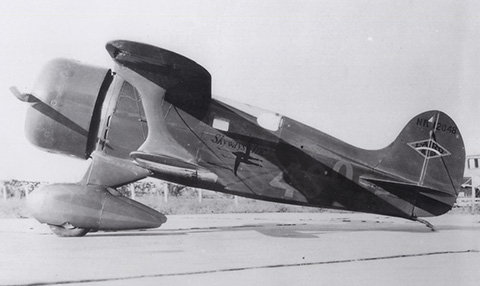

The landing gear was changed considerably with the rigid aerodynamic cross member eliminated and a tension wire substituted at the top of the wheels. Two Cleveland pneumatic struts were used for each wheel permitting a maximum shock travel of 4 in. The wheels and struts were completely streamlined which increased the high speed performance considerably. The landing gear tread was 4 ft. 5 in. The ship was equipped with 650xlO Aircraft Products wheels. These wheels were used during the Bendix race and also the Thompson race. It had been planned to use 20x4 wheels and smaller wheel pants during the Thompson but time did not permit the change.

A direct drive engine was used for the Bendix race and it was planned to install a geared engine for the Thompson, but again time did not allow this change to take place. The direct drive engine used a prop of 8 ft. 3 in., while the geared engine used a 9 ft. prop. The engine turned 2400 rpm with the direct drive as opposed to 1600 rpm with the geared drive. Later the geared engine proved to be 30 mph faster than the direct drive.

The empty plane weighed 1580 lbs. and grossed 2482 lbs. fully loaded, giving a wing loading of 27.16 lbs. for every square foot of its 112 sq. ft. of wing. The span of the upper wing was 21 ft. and 18 ft. for the lower wing. The length was 19 ft. 6 in. Fuel capacity was 112 gal. and oil capacity 11 gal.

Doolittle, writing later, remarked that he made the first flight "from the old Aero Club Field, south of the Chicago Municipal Airport. Laird felt or hoped that the high speed would be around 300 mph." The geared Wasp Jr. had been installed for the first flight, its big 9 ft. Hamilton-Standard adjustable propeller set at 37 degrees pitch at the 42 inch station. Doolittle continued, "The airplane ran about a mile and a half before it could be pulled into the air and then flew about two miles more before it picked up sufficient speed to come under complete control. In succeeding flights the propeller pitch was reduced 5" and the take-off was satisfactory though the engine over-revved somewhat. Clearly a case where the controllable-pitch propeller would have solved everything. There did not seem to be any appreciable torque resulting from the large propeller and geared engine except an acceleration torque when the throttle was moved quickly."

Both Jimmy Doolittle and Matty Laird made several test flights over the next few days. The plane proved stable longitudinally and laterally but extremely unstable directionally. This directional hunting increased with speed and Doolittle reported it was barely manageable at speeds in excess of 200 mph. Raoul Hoffman pinned the cause on too much "fin area" forward of the c.g., the culprits being the longer NACA cowl used on the geared engine, the large wheel pants, and the fairing fillets used between the landing gear struts. After removing the wheel pants and strut fairings she flew beautifully but the unclothed under-carriage now caused unwanted drag. To correct the problem the fin and rudder were increased in height about 9 inches, and the wheel pants reinstalled.

Writing in Racing Ramblings, Doolittle commented, "Although the pilot sat on 50 Ibs. of lead shot the airplane was so stable longitudinally that it was difficult to get the tail down in landing and the plane landed fast." In later tests with the direct drive engine and the 8 ft. 2 in. propeller the plane weighed about 75 lbs. less and the landing speed was nearly 5 mph slower. The LC-DW 500 was fitted with complete blind flying instruments. Doolittle, of course, was an old hand at blind flying and would use this experience in the Bendix race.